5. Six Months

August 23rd, 2024

My last entry was March 2nd, nearly half a year ago — it’s incomprehensible to me that much time has passed. Not because it feels like I was writing that entry just yesterday, though the sensation of pits repeatedly dropping in my stomach reading My Cousin Maria Schneider isn’t a distant memory. But time flies when you become complacent. And that’s not a bad thing — I’ve taken on three (!) day jobs to help stabilize my situation and give my life a sense of rhythm, which the three (!) jobs have done. Have I adjusted to living outside of NYC? No, but I accepted in the spring that was never going to happen. And that’s okay. I’ll take acceptance in lieu of adjustment. Looking at apartments in NYC once a week and in Europe once a month are part of the new rhythm.

I’ve wanted to write, truly. But it’s similar to filmmaking where you reach inward and venture into the trenches and bowels of yourself to ultimately be viewed and judged and edited by who else but that same self, yet it’s all, at the end of the day, to be consumed or taken in by someone else; an internal process that can only really be realized once it becomes external, and it’s the promise of that externalization that lights the fire and gives the the entire journey a sense of purpose. What has been unique about this process, the process of making Transmission, is that there are things I cannot talk about publicly — which is great news, because it means tangible moves have been made and that we are toe-dipping outside the world of the wholly DIY; the world I know that is insulated from any semblance of the “industry”. This film will still be made with our bare hands along with some faith and love and favors and maybe a $20 bill if we’re lucky, but we are in the process of welcoming in collaborators who will transform and elevate and challenge the material; helping push and pull us into a place that we could not achieve completely on our own. This is the dream. The dream is not an unlimited budget, it’s finding artists you admire and whose work exists completely outside the realm of your own; whose art you discovered by simply going to the movies one night or by putting on a record on a whim, only to feel something, a resonance with something deeper, something intuitive or visceral or maybe even spiritual. To think back to some of those moments, including a visit to the Howard Gilman Theater on a brisk October weeknight five years ago, and to think that some of these people have now stepped into my life, or maybe more accurately, I’ve stepped into theirs — reach out to people whose work you admire! — has lit a type of fire I don’t think I’ve felt before.

Yet this has made the last six months hard to write about, because even if these entries were to only be read by me, they’re still written with an audience in mind. But maybe I’m overthinking it.

This probably needs a slight adjustment, doesn’t it.

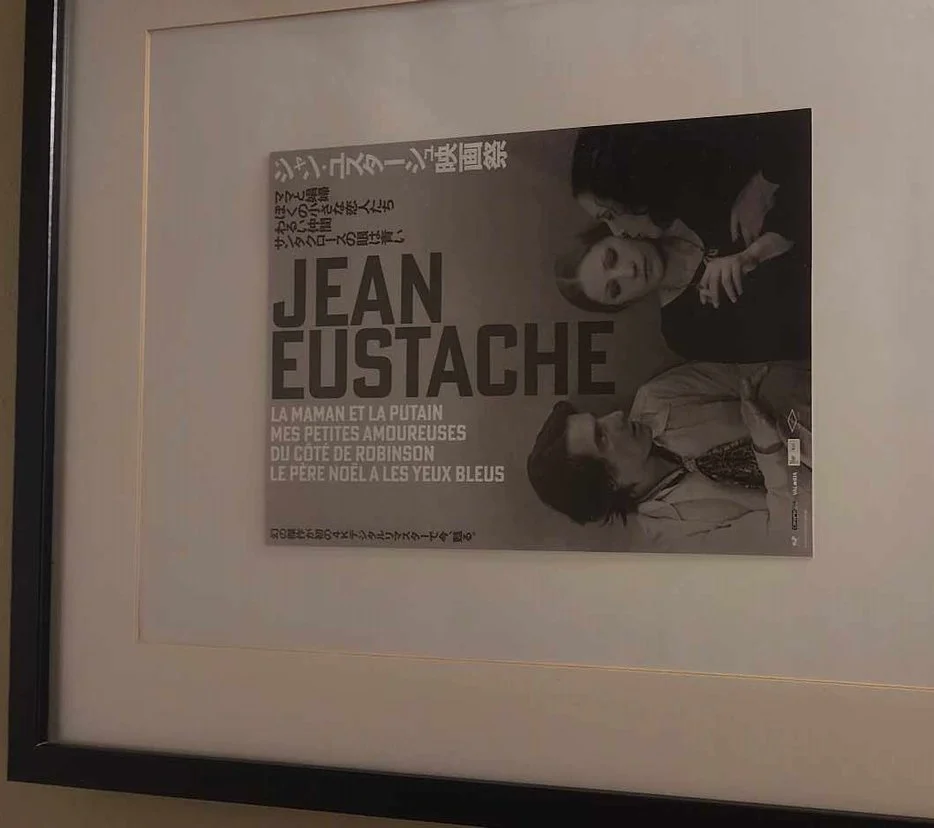

Back in December, only a few weeks of having left NYC and still feeling lots of raw confusion about the move and life changes, which was easiest channeled as anger towards myself for not having the answers I felt I owed myself, I ordered a collection of chirashi posters from Japan. They’re ostensibly flyers placed in cinema lobbies — some are vintage, others newer. I could fit two on the wall alongside my bed, and I could rotate them out, maybe once a month or so. Last night, I was watching deleted scenes from Wim Wenders’ The American Friend — coincidentally, this film was my first vintage poster I ever bought, a Belgian vintage French Grande that now sits folded in my room. There was a deleted scene with the director Jean Eustache in an acting role, only a few years prior to his death, and I realized that my chirashi poster for the restorations of Eustache’s films traveling through Japan has not left the frame closest to my bed since I put it up in December.

I think about Eustache’s legendary film The Mother and the Whore often, not just because of what it is but also what it represents to me. I first saw the film when I was 15 years old, on a digital file that had been ripped from a VHS copy, viewed on a laptop that is barely bigger than my phone today. Viewing conditions that probably would have left the filmmakers distraught, and at age 15 I could barely comprehend the film’s sexual politics, or class politics, or politics-politics. Yet it still made a ferocious impression, and I was deeply affected and swept up by the film, even though I probably couldn’t have told you what it was even “about”. But that’s also what makes these viewings formative — we know that something resonates and we know that we’ve been moved, even if we couldn’t tell anyone why.

Eleven years later, The Mother and the Whore would become the first movie I’d ever see at the Cannes Film Festival — the world premiere of the film’s 4K restoration in the Debussy Theater, with Françoise Lebrun watching directly underneath us in the balcony. So much of the film was “new” to me, yet there was still this feeling underneath of revisiting a familiar, dog-eared text; certain scenes or lines or camera movements activating from my subconscious and hitting me like a boomerang. Jean-Pierre Léaud snuck into the theater during the film and stood for a standing ovation at the end, visibly moved. A few weeks later, my collaborator Cyrus and I saw Léaud in a bar in Paris.

That first viewing of The Mother and the Whore was in the basement of my childhood home; now I’m sleeping directly above the room of that pivotal viewing, down the street from the high school I only lasted one year at; three films later and two (??) occasions of being in the same room with Antoine Doniel. I’m turning 29 next week. I’ve chosen to engage with an industry where so, so much is out of my control, but I can sleep at night knowing I’ve done everything in my own power to will my own work into existence, and that’s all I can ask of myself, as much as I may be eager to engage in the hypotheticals of “what if I’d done ___ differently”. The next stop is trying to couch my own sense of validation and frankly, personhood, in other people’s perception of me and my work. This has been a big year on that front, and the validation has felt beyond good; it’s been humanizing. Yet that maybe points to some room for improvement in finding a healthier relationship with validation.

This is becoming awfully similar to one of the first entries I wrote as I was preparing to move. Cinema as a rock; a boomerang. Maybe art isn’t the only thing we grow around, you could say the same thing about a house or a body of water. But houses crumble and ocean levels are rising; yet it’s easier to see a Jean Eustache film now than it was 10, 20, 30 years ago. More ways to see movies, more ways to expand your mind, more benchmarks to measure how your life has changed. Movies have the power and possibility to be immortal; immaterial. Gena Rowlands may be dead now but her delivery of “I’m almost not crazy now” will outlive this house.

Jean Eustache in The American Friend (1977, Wim Wenders)

That first viewing of The Mother and the Whore was 13 years ago, at age 15. After next week, I’ll be an equal distance of 13 years from age 42 — the age Jean Eustache was when he shot himself after his career had stagnated and he had become partially immobilized in a car accident. I wish he didn’t feel like that was something he had to do. I wish we had more of his voice in the world, more timeless ruminations and investigations into the intersection of love and sex and class and the culture passing oneself by — The Mother and the Whore may reek of 1973, but I guarantee you that situationship is playing out in Dimes Square right now. I’ll soon be closer to the age of Eustache’s death than the age when I first engaged with his work, in this very same household. I don’t know what it means — like the last entry I wrote six months ago, I’m finding lines that I don’t know how to draw, but I know the lines are there. And that’s where it becomes about “the process”; because for me, cinema is identifying these disparate elements that are all connected by *something* and then using the form of cinema to figure out what that something is and then subsequently draw that line, which sometimes happens with narrative logic, other times with emotional logic. That’s what this all is to me, and these journals plant the seeds for me and help me articulate what my relationship to this medium really is as a storyteller, but that’s where the ceiling lies, because if I could write it all out, I’d just do that. But I can’t, and that’s where movies enter the equation.

And that’s where this entry has been heading (though it took some time for me to crack this myself). Because the way I look at structure and storytelling within my own cinema is pretty much the same as the way I look at the rest of the world — I made my first feature when I was barely 20 years old, and even though the subject material was personal to me at the time for a myriad of reasons, the film felt impersonal, even distant. What makes art personal isn’t restricted to autobiography, it’s sharing how you engage with the rest of the world both through the stories you tell and *how* you tell them. The process of writing and developing and later shooting and editing A Muse was figuring this out — you could write a memoir and shoot it like a multi-camera sitcom and lose all sense of personhood or ownership in the material, or you could do the opposite and take that sitcom teleplay and shoot it like a series of Warhol screen tests and find meaning and find yourself in the material through the process and end up with something deeply personal.

Actor Miriam Rizea and a very large dog named Sherlock on the set of A Muse

What I’ve learned more recently is that this extends to everything: the process of getting the movie made is equally personal. Any guidebook to film financing is dated by the time it hits publication, and that’s assuming there is even worthwhile knowledge or advice to divulge, because there’s no obvious or clear path to securing hundreds of thousands of dollars for art, let alone in an industry that seems to be collapsing in real-time. If there was a tried-and-true path, it’d be enshrouded in secrecy so those resources wouldn’t become depleted. So I have to approach all of this like I would my own storytelling — find “what makes sense”, and figure out how to draw a line through all of this. Maybe it’s not that simple. Maybe it doesn’t make any sense. But treating the path towards securing financing like writing a spec script makes even less sense.

I’m going to try and write more and share the process through a more introspective angle, and I will share what I can when I can. I’ll be writing more about having traveled to Cannes in May, as well as sharing an illuminating conversation that I shared with a filmmaker friend this past spring. But right now, I’m enjoying the rain and autumn weather in the summer, and I’m eager to take a look at my Jean Eustache poster before going to sleep tonight. More soon. If you’re reading this, it’s likely because you know me and have stuck with me. Thanks for sticking with me.